- Home

- Alan MacDonald

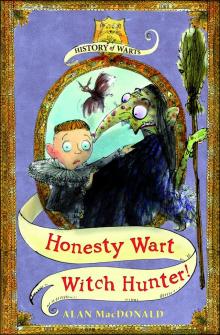

Honesty Wart

Honesty Wart Read online

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1 Worry Wart

Chapter 2 Granny Wart

Chapter 3 Night Visitors

Chapter 4 A Hairy Moment

Chapter 5 The Whiff of Trouble

Chapter 6 In the Soup

Chapter 7 Witchfinder

Chapter 8 Saving Gran

Chapter 9 A Bit of a Flap

Chapter 10 How to Spot a Witch

Chapter 11 That Sinking Feeling

Chapter 12 Gloomy Christmas!

Other titles in the History of Warts series

Foreword

by

Professor Frank Lee Barking (M. A. D. Phil)

Since the dawn of time members of the hapless Wart family have been dogged by disaster. From facing flesh-eating ogres to grappling with gladiators and being kidnapped by pirates, Warts have looked Death in the eye and lived to tell the tale. Now, thanks to years of painstaking research, and literally hours of daydreaming, I am proud to bring you the absolutely true and epic saga of …

The History of Warts

Chapter 1

Worry Wart

‘For all your good and gracious gifts we thank thee, O Lord.’

‘Amen,’ said Honesty Wart, opening his eyes.

‘Amen,’ chorused his sisters, Mercy and Patience, whose prayers always went on longer than anyone else’s.

Honesty’s mum removed the lid of the dish on the table. Inside was a mess of dull brown splodge. It didn’t look like meat, it looked like … well, Honesty tried not to think what it looked like.

‘Turnip mash,’ said Mum. ‘Pass your bowl.’

Honesty watched as she dolloped a spoonful into his bowl and banged it down in front of him. He stared at the splodge, watching the steam slowly rising from it.

‘Something the matter?’

‘No,’ said Honesty. ‘It looks … um … nice.’

‘He doesn’t like it,’ said Mercy.

‘I do!’ said Honesty.

‘He doesn’t. We like it, don’t we, Patience?’

‘We like everything,’ said Patience.

‘I think turnip’s delicious,’ said Mercy.

Honesty glared at his two little sisters. In their dull grey dresses and white caps they looked like identical twins.

‘Eat up, lad,’ said Dad, giving him a friendly nudge. ‘Turnip’s good for you. Make you big and strong.’

‘Better get used to it,’ warned Mum. ‘It’s all you’ll be getting for the next two weeks.’

‘Why?’ asked Honesty.

‘Ask your father.’

‘Why, Dad? Didn’t you get paid again?’

‘’Course I got paid,’ Dad replied, not looking at him. ‘Just not in shillings and pence.’

‘A sack of turnips!’ Mum snorted. ‘For two weeks’ labour.’

‘Not any old turnips,’ said Dad. ‘Samuels said they’re the best turnips you’ll ever taste. He was doing me a favour.’

Mum shook her head at him. ‘You’re a simpleton, William Wart. I should have seen that when I married you.’

Dad caught Honesty’s eye and turned his mouth down at the corners. Honesty tried not to laugh. His mum didn’t approve of laughter. Not at the table, not in the house. There were a lot of things Mum didn’t approve of. A verse hung on the wall to remind them of their Christian duty. It said:

‘Let me do my work this day

Waste no time on fun and play,

Speak no ill and tell no lie,

Pray and toil until I die.’

Honesty felt depressed every time he looked at it. He chewed on his mashed turnip. It tasted disgusting. Two weeks of turnips for breakfast, lunch and dinner, he thought. Boiled turnip, stewed turnip, mashed turnip – he’d probably get turnip to take to school.

At least there was Christmas to look forward to. People in the village of Little Snorley didn’t get excited about much. Most of them were Puritans like Honesty’s family, so excitement was frowned upon. They read their Bible, said their prayers and went to church twice on the Sabbath. They didn’t sing, dance or gamble, and kept away from ungodly places such as taverns or theatres. But Christmas was different. Christmas was the one day of the year when everyone in the village came together to celebrate. There would be a log blazing in the hearth and holly and ivy hanging from the rafters. Best of all, thought Honesty, there would be Christmas dinner: mince pies, plum pudding and, if he was lucky, a roast goose as big as a football.

‘When are we getting the goose?’ he asked.

Mum frowned at him. ‘What?’

‘For Christmas dinner. The goose.’

His mum and dad exchanged looks. ‘Haven’t you told them yet?’ asked Mum.

Dad looked sheepish. ‘I was going to. I just … well, haven’t got round to it.’

Honesty could tell that bad news was coming. Even Mercy and Patience had stopped eating their supper. Had somebody died? Were they having boiled turnip for Christmas dinner?

‘What?’ he asked. ‘Tell us what?’

‘Honesty, lad.’ Dad laid a hand gently on his shoulder. ‘Don’t take it too hard, but well … there isn’t going to be any Christmas this year.’

‘No … Christmas?’ Honesty thought his dad must be joking, except Mum didn’t approve of jokes.

Mum pursed her lips. ‘Parliament passed a law. Christmas is banned – and a good thing too if you ask me.’

‘But we always have Christmas! It’s the best day of the year! The only day we’re allowed to have fun!’ Honesty knew he was raising his voice, but he couldn’t help it.

His mother glared and pointed her spoon at him. ‘Fun? Playing at cards and dice? You call that fun? Drinking and brawling in the streets?’

‘But Mum, we don’t do any of that,’ protested Honesty.

‘We don’t but that won’t stop other folk. In London I hear they go to the theatre on Christmas Day. Some of the actors are women!’ Mum gave a shudder.

Dad shook his head sadly. ‘Surely it can’t do any harm to give the children a little present, Agnes.’

‘I don’t mind not getting a present,’ said Mercy nobly.

‘No,’ said Patience. ‘It’s better to give than to receive.’

‘Presents?’ said Mum, going red in the face. ‘You sit there and talk about presents when all we have to eat is turnip?’

‘I know,’ said Dad, ‘but –’

‘What does it say in Scripture? “Go to thy work, thou sluggard.”’

‘What’s a sluggard?’ asked Patience.

‘It’s a very big slug,’ answered Mercy.

Honesty tried to get back to the point. ‘But Mum, if we don’t have Christmas, what will we do all day?’

‘The same as we do any other day,’ snapped Mum. ‘We’ll work and pray and go to bed. Now, are you eating that turnip or letting it go cold?’

Honesty ate the rest of his meal in silence. Never in his life had he felt so utterly miserable. He was used to disappointment but he had been looking forward to Christmas for weeks and weeks, crossing off the days on the calendar. Now 25th December would be like any other day of the year – deathly dull. Life couldn’t get any worse. Or so he thought.

‘Honesty,’ said his mum, ‘take some supper up to your gran.’

Chapter 2

Granny Wart

Honesty slowly climbed the stairs to his gran’s room, taking care not to drop the bowl of lukewarm turnip mash. He stood on the landing, summoning his nerve. The truth was, he wasn’t sure if Gran was quite right in the head. She was a bit odd. In fact there were times when she gave him the creeps.

‘Gran, it’s me! I’ve brought your supper!’ he called.

The door creaked open when he pushed it. There was no sig

n of Gran. He stepped into the dark, stale-smelling room and set down the bowl of food on a pile of books. He had never understood why Gran got a bedroom all to herself. The house only had two rooms but Honesty had to sleep downstairs with his mum, dad and sisters.

And why did Gran clutter her room with so many strange things – things that he didn’t like to look at too closely? Every shelf was piled high with objects, books and papers. There was a red toadstool growing in a jar. Dozens of other glass jars and bottles jostled for space on the shelves. He peered inside at bits of bone, cobwebs and frogspawn. There were tiny bottles containing cloudy liquids of every colour. A candle on the mantelpiece gave out a dim light but never seemed to burn any lower. Dusty books and charts covered the floor, piled high on top of each other. On one pile a pair of yellow eyes snapped open and blinked at him.

‘CROOOARRRK!’

Honesty jumped backwards in surprise. It was Gran’s pet toad, Merlin.

‘See anything that interests you?’ Honesty spun round to find Gran sitting in her high-backed chair. She must have been there all the time, watching him. He suspected she did this kind of thing deliberately. Sometimes he wondered if she appeared out of thin air – you could never be sure with Gran.

‘Did he frighten you, my sweet?’

‘No, no,’ said Honesty. ‘I just didn’t see him.’

Gran scooped up Merlin in her hand. ‘I was talking to him, not you,’ she said. ‘There, there, my sweetheart, don’t you worry. I won’t let him harm you.’

This was another strange thing about Gran. She talked to Merlin as if he could understand every word.

‘I brought your supper,’ said Honesty, keen to get away as soon as possible. ‘It’s got a bit cold.’

Gran sniffed the brown mush. ‘What’s this meant to be?’

‘Turnip.’

‘Blech! Where’s my mutton broth? I always have broth.’

‘It’s turnip tonight, Gran. Try it.’

‘Don’t talk rubbish! Put it down, boy, before you drop it.’

Honesty did as he was told. He watched his grandmother as she stroked Merlin’s horny back. Her skin was as wrinkled as tree bark, hanging in great pouches under her eyes. Her grey hair hung over her shoulders in tangles and knots. Her nose was hooked like a hawk’s beak, which made him feel she might peck him if he got too close. Honesty didn’t know how old she was, but at a guess he would have said one hundred and sixty.

‘Come closer, where I can see you better.’ She beckoned with a long fingernail.

Honesty edged towards the door. ‘I can’t stay long, Gran. I think Dad needs me downstairs.’

‘Rubbish! Stay a minute and talk to your old gran. Come here.’

Gran was smiling at him – a thin, crafty smile showing her three yellow teeth – two on the bottom, one on the top. She had a moustache too and curly white hairs sprouting from a mole on her chin.

‘What’s the matter? Something’s upset you, hasn’t it? I can see.’

‘No, I’m fine,’ said Honesty. Another disturbing thing about Gran was the way she could read your mind. It was whispered in the village she had second sight. Honesty wasn’t exactly sure what this meant, but he was pretty sure it wasn’t normal.

‘Come now, you can tell your gran. What’s the trouble, my dear?’ she crooned.

Honesty took a step forward. Gran’s hand snaked out and seized his wrist, pulling him close. For an old woman she had a surprisingly strong grip.

‘Ow! You’re hurting, Gran!’

‘There now. I won’t bite. Tell your gran all about it.’

Honesty sighed. ‘You know it’s Christmas in three weeks?’

‘What of it?’

‘Mum says it’s banned this year.’

‘Banned? What do you mean, boy? We always have Christmas.’

Honesty explained what his mum had said about the law Parliament had passed. Gran cackled with laughter. ‘Ban Christmas? The fools! They might as well try and ban dancing.’

‘They have,’ said Honesty.

‘Since when?’

‘Since last year. You can go to prison for dancing.’

‘The world’s gone mad.’ Gran shook her head. She still had hold of his wrist. ‘And this is what’s troubling you, is it? You’ll miss your Christmas dinner?’

Honesty nodded glumly. ‘We were going to have goose,’ he said. ‘Dad promised. And mince pies and plum pudding.’

‘Then have them we will. Who’s going to stop us, I’d like to know?’

‘But it’s the law, Gran! Mum says Christmas will be just like any other day.’

‘Don’t you listen to your mother,’ said Gran. ‘Listen to me. If I say we’ll have Christmas, then we will.’

‘But how, Gran?’ asked Honesty.

‘You leave it to me. I have my ways.’ Gran’s finger tapped the side of her bony old nose. ‘There’s things you know nothing about. Things they don’t teach you at school.’

‘What kind of things?’ asked Honesty.

Gran’s eyes widened. ‘Secret things.’

‘Anyway,’ Honesty said, backing towards the door, ‘thanks for the chat, but I ought to be getting back.’

Gran’s bright little eyes flashed at him. ‘Not so fast. I haven’t finished yet. You want my help, then you’ll have to do something in return.’

‘What?’ asked Honesty.

Merlin had crawled up Gran’s chest and was now squatting on top of her head. It looked like she was wearing an ugly brown bonnet.

‘Oh, you’ll see. Nothing difficult. I can’t get about like I used to, not with my poor old legs.’

Honesty weighed it up. He should have guessed his gran was up to something.

‘Christmas dinner,’ she said, smacking her lips together. ‘Best meal of the year. Think of that fat roast goose. I like a leg myself, a nice juicy leg …’

Honesty’s mouth was watering. ‘All right!’ he cried. ‘I’ll do it. As long as it’s nothing … you know …’

‘What?’

‘Magic.’

Gran narrowed her eyes at him. ‘Magic? Who said anything about magic?’

Chapter 3

Night Visitors

Honesty lay awake. The midnight chimes of the church clock were striking. He could hear his little sisters breathing from beyond the curtain that divided the room. His dad was snoring as usual.

It’s not as if I’m doing anything wrong, he told himself. I haven’t told a lie. I’m only helping Gran. Honesty had a dread of telling lies, probably because of his name.

Gran had said that the visitors would arrive before midnight. She hadn’t told him who they were. All he had to do was show them upstairs without waking anyone else. All the same he felt guilty: his mum said he should never let strangers into the house. And why were Gran’s friends coming in the middle of the night? Were they robbers? Murderers? Even worse, witches? What if they were looking for small boys who would fit nicely in a cooking pot?

Plunk! Plunk!

He held his breath. Someone was throwing pebbles against the window. The witches were here already. He pulled his blanket over his head, hoping they’d go away.

Plunk! Plunk! CRACK!

If they carried on like this, they’d smash the window and wake the whole house. Taking the candle from the mantelpiece, Honesty stole to the door in his bare feet. His hand was trembling as he drew back the bolt and opened the door an inch.

It took a few moments to make out their faces in the dark. He was relieved to see two neighbours from the village: Ratty Annie and old Tom Turner.

‘Let us in,’ hissed Ratty Annie. ‘We’re freezing to death.’

Honesty led them upstairs. He knocked softly on Gran’s door and after a moment it opened.

‘You’re late,’ grumbled Gran. ‘Close the door behind you.’

With the four of them inside, the little room was crowded. Tom Turner had to duck his bald head to avoid thumping it on the ceiling. Gran settled herself in her

high-backed chair and stared at her visitors.

‘Well, what have you brought me?’

Ratty Annie stepped forward. She was a dirty-faced girl a few years older than Honesty. She fumbled in her pockets, bringing out two brown eggs and something she held up by its tail. A rat. ‘Brought you a nice big ’un. Caught him fresh this morning,’ she said.

Her dad was the village rat catcher and she sold the dead rats for a farthing each. That was why everyone called her Ratty Annie.

‘Thanks, but you keep it,’ said Gran. ‘I’ll just take the eggs.’

‘Sure?’ said Ratty Annie. ‘I’ll save him for later then. Make a nice rat stew for Dad’s supper tomorrow.’ She slipped the rat back into her pocket.

Tom Turner had brought a gift of five green apples. ‘I had six,’ he explained, ‘but I got hungry on the way. Saved you the apple core though.’

‘Thoughtful of you,’ said Gran. She put the eggs and the apples into a bowl.

‘So, you want my help?’

Ratty Annie lowered her voice. ‘They say you have powers. The second sight.’

Gran was stroking Merlin in her lap.

‘They say lots of things,’ she said. ‘What is it you want?’

Ratty Annie chewed on a lock of her hair and looked at the ground. ‘There’s a boy.’

‘Ahhh, a boy.’ Gran nodded.

‘I see him in church every Sunday. He sits across the aisle. But he never pays me no attention. Except once he caught me staring and called me a ratty old fleabag.’ She glanced at Honesty, daring him to laugh. ‘I want … him …’

‘To like you?’ smiled Gran.

‘Why shouldn’t he?’ demanded Ratty Annie, glaring furiously. ‘I’m as good as the rest, ain’t I?’

‘No one said you’re not.’

‘My dad reckons I’m pretty as a plum.’ She twirled a lock of dirty hair round her finger and glanced at Honesty. ‘You laugh and I’ll land you one.’

‘I’m not laughing,’ said Honesty, trying to look serious. He had never imagined that Ratty Annie could be in love. Harder still was imagining anyone falling in love with her – keeping dead rats in your pockets wasn’t exactly romantic.

Zombie!

Zombie! Cupcake Wars!

Cupcake Wars! Monster!

Monster! Euuuugh! Eyeball Stew!

Euuuugh! Eyeball Stew! Superstar!

Superstar! Superhero School

Superhero School Pong!

Pong! Jackpot!

Jackpot! Aliens!

Aliens! Fangs!

Fangs! Fleas!

Fleas! Kiss!

Kiss! Smash!

Smash! Mud!

Mud! Trolls Go Home!

Trolls Go Home! Disco!

Disco! Goat Pie

Goat Pie Yuck!

Yuck! Fetch!

Fetch! Ditherus Wart

Ditherus Wart Horror!

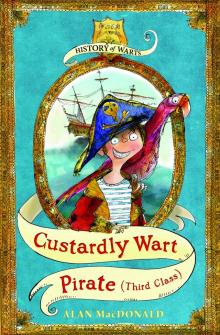

Horror! Pirate!

Pirate! Burp!

Burp! Worms!

Worms! Puppy Love!

Puppy Love! Ouch!

Ouch! Alien Attack!

Alien Attack! Toothy!

Toothy! Sir Bigwart

Sir Bigwart Germs!

Germs! Trolls United

Trolls United Rats!

Rats! Thunderbot's Day of Doom

Thunderbot's Day of Doom Crackers!

Crackers! Curse of the Evil Custard

Curse of the Evil Custard Arrrrgh! Slimosaur!

Arrrrgh! Slimosaur! Honesty Wart

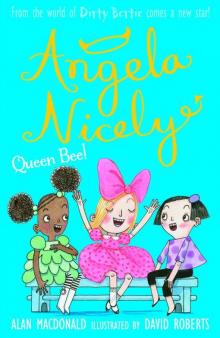

Honesty Wart Queen Bee!

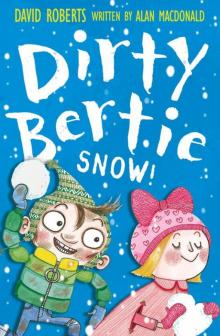

Queen Bee! Snow!

Snow! Custardly Wart

Custardly Wart Trolls on Hols

Trolls on Hols Pants!

Pants! Angela Nicely

Angela Nicely Loo!

Loo! BOOOM!

BOOOM! Bogeys!

Bogeys!